stc’s Transport Network Evolution White Paper

Available Languages

Bias-Free Language

The documentation set for this product strives to use bias-free language. For the purposes of this documentation set, bias-free is defined as language that does not imply discrimination based on age, disability, gender, racial identity, ethnic identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and intersectionality. Exceptions may be present in the documentation due to language that is hardcoded in the user interfaces of the product software, language used based on RFP documentation, or language that is used by a referenced third-party product. Learn more about how Cisco is using Inclusive Language.

- US/Canada 800-553-2447

- Worldwide Support Phone Numbers

- All Tools

Feedback

Feedback

IP/optical convergence with automation promises significant operational, sustainability, and financial benefits for Communication Service Providers (CSPs). To evaluate these claims, stc engaged with Cisco to undertake a multiphase proof-of-concept trial and Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) evaluation of the Cisco® Routed Optical Network automation solution.

Phase 1 of these trials demonstrated that IP/optical convergence using the Cisco Routed Optical Networking automation reference architecture contributed significantly toward stc’s key goals for its long-term transport infrastructure:

1. TCO reduction: Efficiently utilizing network resources and significantly reducing duplication

2. Sustainability: Reducing stc’s carbon emissions and improving energy efficiency

3. Greater automation and operational simplicity: Achieving closed-loop automation for on-demand real-time resource allocation and fault remediation across the entire network infrastructure

4. Innovation: Providing the ability to rapidly develop and launch innovative services for customers

The proof of concept also identified operational changes that will need to be supported through careful transition planning. Phase 2 will extend the evaluation to multivendor IP and optical environments and will be the subject of a separate white paper.

Introduction: stc’s innovation and transformation journey

stc is a pioneer and digital champion in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region and is the leading telecommunication service provider in Saudi Arabia. stc’s focus on innovation and evolution helps ensure it remains at the forefront of change. Technology transformation is a significant enabler of stc’s overarching strategy: to be a world-class digital leader that provides innovative services and platforms that enable the digital revolution for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the MENA region.

stc’s fixed and mobile broadband traffic continues to be predominantly IP-based services, and consequently the next-generation network architecture should be optimized for transporting mostly IP traffic. Transport infrastructure strategy is therefore pivotal to the success of stc’s digital transformation journey of becoming the regional hub connecting the three continents: Asia, Africa, and Europe.

Similarly, to other operators globally, stc has designed, built, and operated its IP transport and optical transport infrastructure as separate network layers, with separate management systems and teams. This approach made sense when IP networking was just one of several services running over a shared optical transport layer and when the only way to decouple optical technology upgrade cycles from IP networking technology upgrade cycles was through separation.

However, the advancements in optical transport plane technologies, together with the maturing of open standards–based centralized control planes, are enabling new converged transport architectures. Based on this, stc has engaged with Cisco in multiphase proof-of-concept trials and TCO evaluation of the Cisco Routed Optical Network solution.

Two separate network layers: Posing limitations for automation, sustainable performance, reliability, and scale

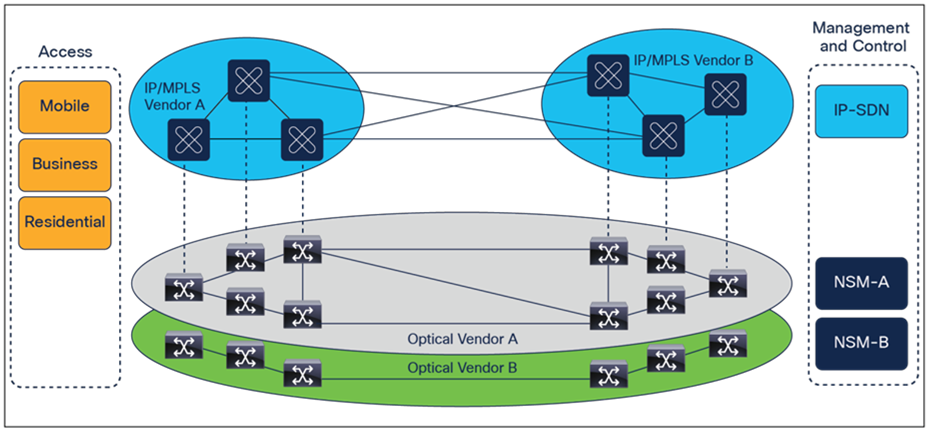

stc currently deploys a multivendor and multilayer transport network:

● The IP transport layer is deployed as interconnected, vendor-specific, MPLS-enabled regions with a joint Software-Defined Networking (SDN) controller.

● The optical layer is deployed as multiple parallel optical transport networks of metro and long-haul (inter-region) links consisting of Dense Wavelength-Division Multiplexing (DWDM) optical network and Reconfigurable Optical Add-Drop Multiplexers (ROADM). Separate vendor-specific Network Management Systems (NMS) and associated tools are used to manage these parallel networks in the optical domain.

stc's multilayer, multivendor transport topology

stc has identified fundamental inefficiencies and pain points with the current transport architecture, which need to be addressed in pursuit of its four key goals.

Having an overall architecture that is composed of separate layers with siloed infrastructure results in limited awareness of traffic behaviors across layers. This means greater complexity for the network operations teams to manage.

● Disparate optical and IP transport domains result in the manual stitching of services across network domains and vendors. This inhibits automated operations (remediation) and results in longer service delivery lead times.

● The current Operational Support System (OSS) responsible for the network (topology and inventory) discovery, service provisioning, fault management, and performance monitoring across the IP and optical transport layers is also siloed. It requires extensive bespoke integration so that the network teams can complete their tasks.

● The use of proprietary APIs toward the OSS layer creates a bottleneck that results in complex, lengthy, and costly integration cycles and hinders network automation.

● This also means that any new transport service introductions are restricted to proprietary vendor product roadmaps, many of which are still costly and require further bespoke deployments with said vendors to launch them.

The complexity and fragmentation result in higher overall TCO and resource inefficiencies and means that stc is faced with having to make compromises on costs, operational simplicity, and the speed of innovation. For example:

● There is a high dependency on proprietary vendor solutions for the optical plane, so historically multiple parallel/duplicated deployments were needed to maintain competitive supply and business continuity.

● Overlapping resiliency schemes in each networking layer contribute to the inefficient utilization of network resources.

These complexities represent challenges that all CSPs face in achieving service-driven, end-to-end, closedloop automation across their network infrastructure. The high TCO associated with this network architecture hinders scaling the network to cost-efficiently meet the capacity demands of IP services. The inherent complexity in the existing architecture is also problematic for operations teams to optimize and troubleshoot across fragmented, siloed systems. Figure 2 below shows a simplified view of how stc’s routing platforms are currently interconnected via ROADM-based Optical Line Systems (OLS) through vendor-specific Optical Terminals (OT). Both layers (IP and optical) are independently controlled and managed and are unaware of each other. The OLSs are managed through proprietary Network Management Systems (NMS), while the IP nodes are controlled via an SDN controller.

stc’s current high-level network architecture

IP and optical convergence: Validating the potential for enabling stc’s key transport network goals Convergence of IP and optical layers promises to simplify network architecture through greater cohesion between IP and optics. This could potentially offer greater resilience and reliability with a smaller physical, energy, and environmental footprint.

Benefits of a converged IP and optical network

The diagram above outlines the expected key benefits from converged software-defined transport networking:

● Better resource utilization, lower TCO, energy, and emissions: Right-sizing of the network, reducing the number of devices required (including the number of routers), the space to house them, and the Uninterrupted Power Supply (UPS) and Air Conditioning (AC) needed. Streamlining operations should contribute to less duplication in capital deployment and lower CapEx and OpEx, as well as power efficiency gains and reduction in the total carbon footprint.

● Greater automation, network reliability, and ease of management: Achieving cohesion through a unified architecture can unlock much greater opportunities for end-to-end automation and orchestration. Automation is a key area where telcos can see the most significant sustainability benefits. This can lead to greater network reliability with a significant increase in service assurance process efficiency. Eliminating unnecessary complexity and moving away from a siloed architecture means the overall transport network becomes easier to manage and enables much greater end-to-end automation. For network operations teams, it can mean a significant reduction in time for move and add changes within the transport network.

● Greater network and service innovation: Through greater simplification and automation, network convergence should accelerate development cycles and reduce the costs associated with developing, testing, and deploying new network services and/or end-user services. Lower-cost, faster innovation not only means more viable innovation, but also means a change in innovation model, to a more agile, lower-risk, customer-centric, fast-fail approach needed to drive growth—for example, with dynamic end-to-end network slicing.

● Less product maintenance: By deploying a converged solution, there’s less equipment required and, in theory, no need for separate IP and optical networking tools, skills, or inventory. The transport network could be centrally managed by a common management layer, combining the network layers, services, and network domains into a single SDN. stc anticipates challenges in achieving this across a multivendor environment, which will be tested in the phase 2 PoC.

Significant TCO and sustainability benefits are projected from converging IP and optical layers

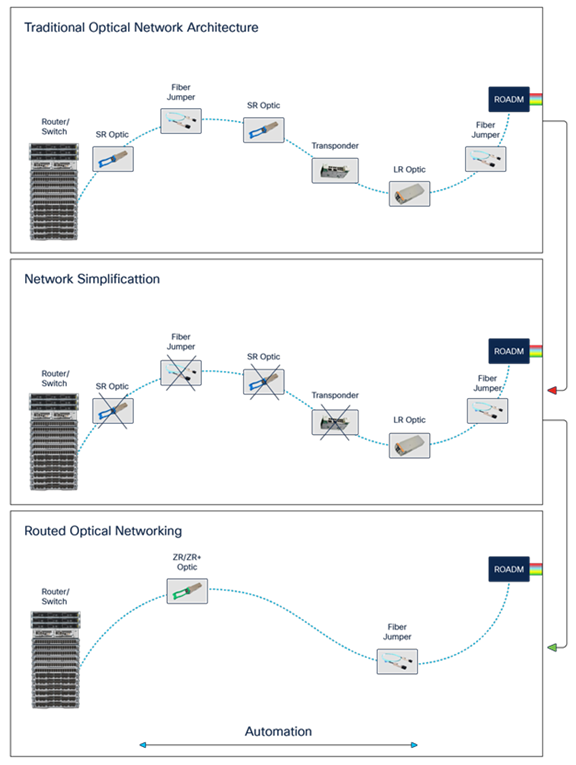

Mirroring the technical proof of concept described later in this paper, Cisco and stc built a TCO model comparing two architectures for a metro use case:

1. The Present Mode of Operation (PMO) with separate physical layers: Each IP router port is connected to the OLS via a dedicated transponder.

2. Converged IP and optical layers: Where each IP router port is connected to the OLS via a pluggable coherent DWDM QDD-SFP, eliminating the need for a separate transponder layer.

Figure 4 compares integrated DWDM interfaces with current architecture PMO.

Present mode of operation vs. converged IP and optical layers

The TCO calculation was undertaken based on stc’s multivendor OLS network.

The CapEx savings are driven by the following:

● Removal of four gray pluggable optical interfaces per link: two in the source node and two in the destination node.

● Removal of two transponder ports per link: one in the source node and one in the destination node.

● Removal of the transponder chassis in both source and destination nodes.

Similarly, the above simplification provides OpEx savings:

● The removal of gray pluggable optics, transponders, and chassis gives benefits both in terms of power consumption and footprint, the latter primarily due to the complete removal of the transponder chassis.

In addition, cabling is simplified as 50% of the required patch cords are now removed.

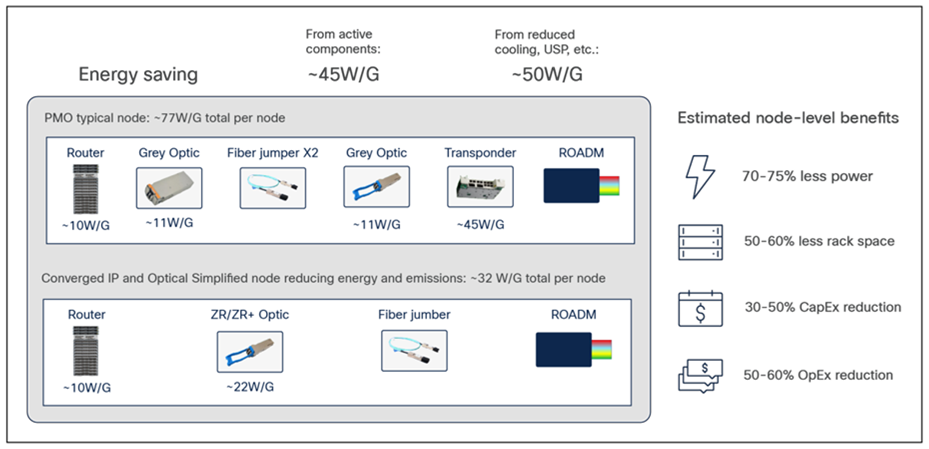

Integrating the transponder into the router resulted from the advancement of Network Processing Units (NPUs) evolution in IP routers. Based on Cisco inputs, figure 5 sets out the estimated energy, CapEx, and OpEx savings at a node level.

Indicative node-level reductions through convergence and in energy, CapEx, and OpEx

The TCO evaluation expanded on the simple node-level calculation in Figure 4 to include:

● Total number of aggregation nodes N

● Required traffic per aggregation node

● The number of years modeled

● Traffic growth per year

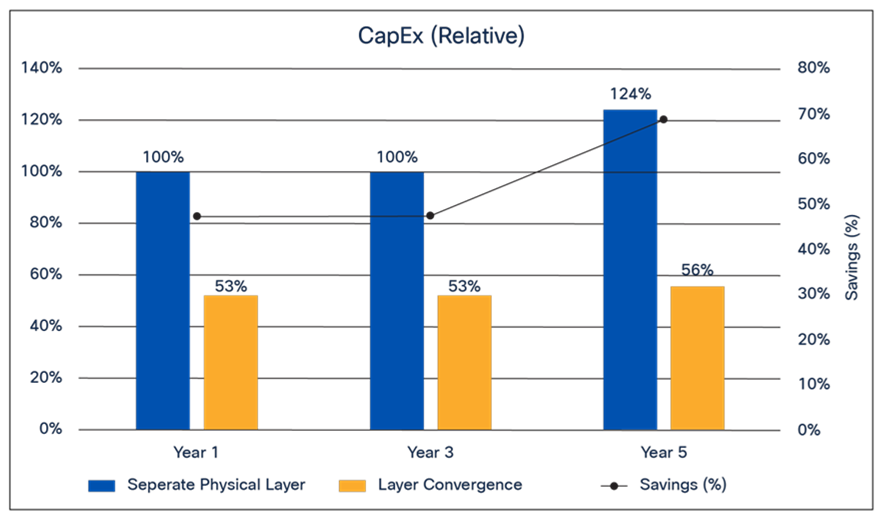

The below figure shows the summary of projected CapEx spending over five years (only three years are

shown – years 1, 3, and 5). To anonymize the data, we used year 1 CapEx of the PMO Separate Physical Layers case as our reference (100%). In this way, we can easily see the additional investments required each year due to traffic increases and the savings of the Layer Convergence case. This shows that, on average, integrating the transponder function into the router provided 50% CapEx savings over five years.

Separate physical layer vs. layer convergence – CapEx savings (relative)

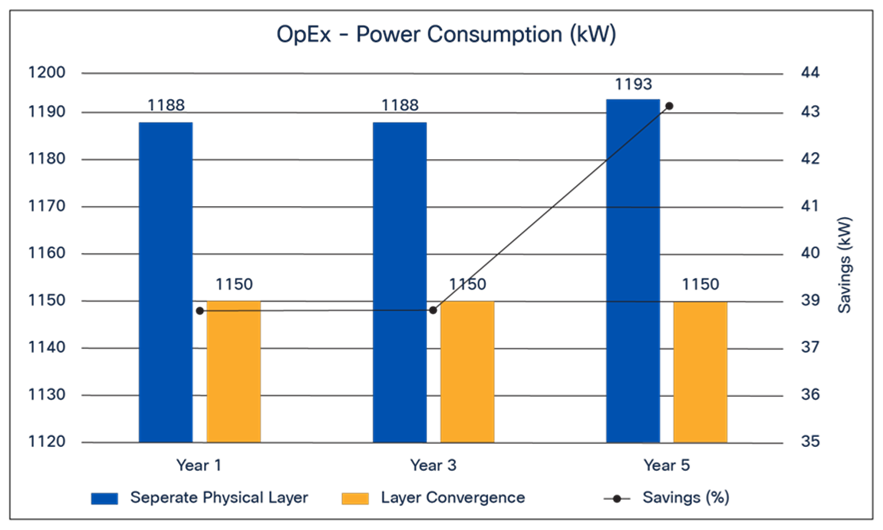

Similarly, we calculated the network's total power consumption required by the two cases. Since the L3 is shared in both cases, this wasn’t included in the model. The L0, which includes the OLS, was included in the total power consumption.

The average savings in a network of roughly 50 aggregation nodes (N = 50) is around 40 kW, as shown in Figure 7.

Separate physical layer vs. layer convergence – OpEx savings (power consumption)

We also projected the total number of Rack Units (Rus) required at the network level to support the two architectures. The results (in Figure 8) indicate that layer convergence is projected to require 120 fewer RUs across the network compared to the current approach of separate transport layer infrastructure.

Separate physical layer vs. layer convergence – OpEx savings (rack units)

By combining IP and optical layers, we can significantly reduce space, power, and HVAC needs, resulting in less build-out of passive infrastructure and a reduction in recurring costs. This is a significant reduction in both the physical footprint and carbon footprint, including embedded carbon from new facilities.

In addition to IP and optical direct TCO benefits, automation brings major TCO benefits via:

● Service provisioning: Shift from manual to automated provisioning.

● Service assurance: Reduction in tickets being exchanged between teams. Less people required to diagnose root cause. Reduction in service impacting events and associated revenue leakage.

In summary, the TCO analysis provides a strong indication that there are significant CapEx, OpEx, and sustainability benefits that can be achieved by moving to a converged IP and optical architecture.

Furthermore, the above TCO analysis doesn’t include operational and performance benefits covered in the sections below. These include benefits arising from:

● Greater network and service innovation

● Greater automation and ease of management

◦ Real-time, end-to-end topology discovery

◦ Simplified, accelerated network service design and provisioning

◦ Improved reliability, network troubleshooting resolution, and repair (service assurance)

● Rationalized infrastructure through multilayer restoration and network planning

The PoC exercise described below highlighted the need for process redesign and revised operational demarcation between teams. stc will also need to incorporate plans for any non-IP services that won’t be decommissioned. These additional factors can be quantified and included in a full business case for the transition to greater convergence.

Recent developments in the optical forwarding and transport network control planes have enabled IP and optical convergence. Progress in standardization and specifications by industry working groups, including papers published by the Telecom Infra Project (TIP), have highlighted the options, use cases, and requirements for achieving IP/optical convergence. These include:

● The installation of a new generation of DWDM optical transceivers directly plugged into routing platforms and being able to control and manage them via SDN controllers.

● Range in options for the disaggregation of optical transport systems using open and standard APIs between the different architectural components.

● Greater interoperability between new pluggable modules because of specifications and multisource agreements such as the OIF Common Management Interface Specification (CMIS) and TIP Transponder Abstraction Interface (TAI) as well as the OIF Implementation Agreement (400ZR) and OpenZR+ multisource agreement (OpenZR+ and Next-Gen ZR+).

● Multivendor, standards-based automation stack.

This new generation of multisourced interoperable coherent pluggable DWDM optical transceivers directly integrate into next-generation router platforms. These ultimately enable a network design referred to as IPover-Wavelength-Division-Multiplexing (IPoWDM)–based architecture for general IP and optical convergence.

The table below provides a brief overview of the key traits of three pluggable transceivers: 400ZR, OpenZR+, and Next-Gen ZR+.

Table 1. Overview of the open coherent pluggable optical transceivers

|

|

400ZR |

OpenZR+ |

High Power ZR+ |

|

| Specification |

OIF Implementation Agreement |

OpenZR+ Multi-Source Agreement |

||

| Target use case |

Pt-Pt, single--span |

Pt-Pt multi-span ROADM |

||

| Type of client interface (client traffic) |

Purpose-built Only supports 400GE |

Programmable Can support 100GE to 400GE |

Programmable Can support 100GE to 400GE can support OTN clients |

|

| Modulation |

Modulation fixed at 16QAM per 400ZR OIF spec |

Flexibility in modulation systems to balance data rate requirements, noise margins and error rate (Supports QPSK, 8QAM, 16QAM) |

||

| SD-FEC (Enables higher data rates and longer distances) |

Signal performance adheres to 400ZR OIF spec CFEC |

Higher optical performance Enabled by open FEC (oFEC) |

||

| Launch power |

c. 10 dBm Requires External Amplification |

c.1 dBm Includes Internal Amplification |

||

| Optical reach |

< 120km only |

Regional and long-haul distances |

||

| Power |

c. 15W |

18-20W |

21-23W |

|

The form factors for the above open coherent pluggable optical transceivers reduce the number of elements in the end-to-end transport chain that need to be planned, installed, and managed, leading to reduced power/space requirements, simplified connectivity, and an overall improved TCO. The possibilities of deploying an IPoWDM router platform equipped with coherent pluggable transceivers were explored by stc with Cisco’s Routed Optical Networking architecture.

To validate the IP-over-WDM concept, stc has embarked on a series of POC trials with Cisco based on its Routed Optical Networking architecture. The objective of the tests was to determine how this architecture simplifies and automates the multilayer transport network architecture with OpenZR+ pluggable coherent optics in conjunction with hierarchical (multilayer) SDN control.

The target use case focuses on a metro ROADM-based optical transport network where intersite fiber distances for interconnecting router platforms are within 120 km, where in-line optical amplifiers are not required with the first generation of ZR/ZR+ pluggables used in the PoC (the next-generation ZR+ doesn’t need amplification), and the effects and impacts on alien wavelength channel transport through an existing Optical Line System (OLS) were expected to be minimal.

The validation was planned over two phases outlined below:

● Phase 1: Testing and baselining the reference architecture for Routed Optical Networking in a controlled environment and defining the core capabilities from the optical plane, control and management plane, and operational model perspectives in an ideal best-case scenario.

● Phase 2: Demonstrating a feasible multivendor and multilayer Routed Optical Networking metro architecture. The second-phase setup introduces third-party IP routing platforms and third-party ROADM-based OLSs from other stc incumbent transport vendors and their respective domain controllers. This phase will determine the current maturity for the support of Routed Optical Networking in stc’s brownfield multivendor metro transport infrastructure and highlight the critical gaps in the optical plane, control and management plane, and the operational model that needs to be addressed.

This section provides a brief overview of the Routed Optical Networking-based architecture adopted for phase 1 PoC and key findings. The phase 2 PoC trial has yet to be completed, and its findings will be the subject of a forthcoming white paper.

As part of phase 1, TIP’s MUST SDN architecture (”Single-SBI” approach via the IP-SDN controller only) was adopted by stc for its lab PoC. The initial tests adopted Cisco infrastructure, but the same automation infrastructure could be used in multivendor IP and optical environments to be explored in phase 2 of the PoC. Open APIs such as NETCONF, REstcONF, OpenConfig, IETF, and TAPI were part of the tests. The following components from Cisco were used in our testbed:

● Cisco Crosswork® Hierarchical Controller (HCO): Multivendor, multilayer, multidomain hierarchical controller that would provide topology visualization, assurance, provisioning, and path computation across IP and optical networks by integrating with the respective domain controllers.

● Crosswork Network Controller: Multivendor IP controller. Provides IP network topology discovery, visualization, transport and service orchestration, path computation, and assurance.

● Cisco Optical Network Controller: Provides optical topology discovery, optical path computation element, provisioning, and assurance.

stc’s Routed Optical Network PoC automation layer setup

Figure 9 shows the automation architecture used in the PoC, which is in line with standards of open architecture automation framework to automate the multivendor and multilayer IP and optical networks. This architecture is targeted to provide end-to-end IP/optical multidomain, multivendor service and network visibility, assurance, topology visualization, orchestration, and path computation.

In partnership with Cisco, stc explored the following use cases for Routed Optical Network management in the stc lab PoC.

1. Real-time, end-to-end topology discovery

Before starting with network provisioning, each domain controller discovered the network topology within its own realm. The tested architecture discovered the cross-mapping between the IP and optical layers. The connections between each router’s OpenZR+ port and the optical line system were correctly identified and displayed.

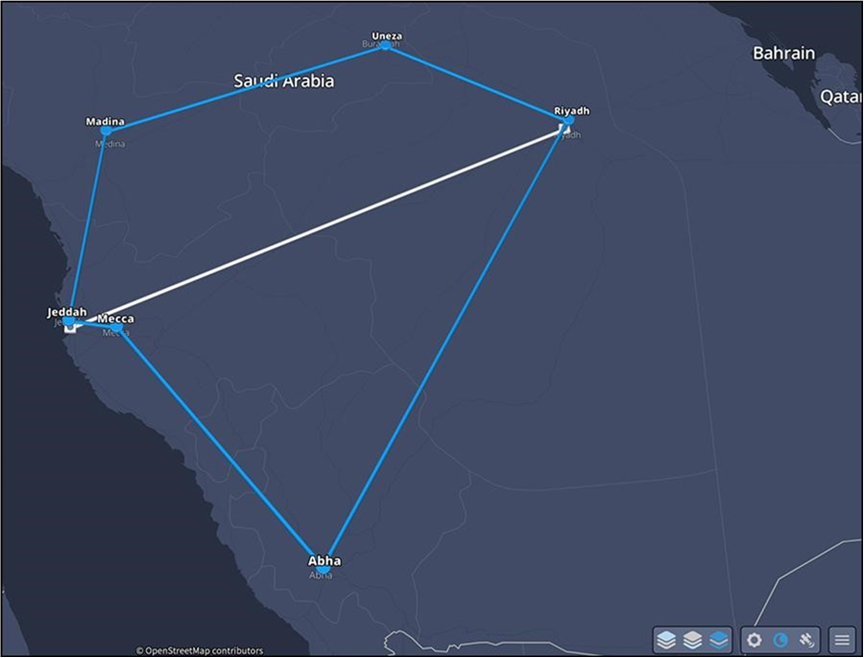

Testbed topology as discovered

Figure 10 shows the IP topology in blue and the optical topology in white. Using two different fibers, a single optical connection is shown between Jeddah and Riyadh. The cross-link between the optical and the IP layers is documented at both Jeddah and Riyadh locations.

Network discovery and multilayer representation are key benefits of the SDN architecture; using the open and standardized APIs, the hierarchical controller built the multilayer topology in almost real time.

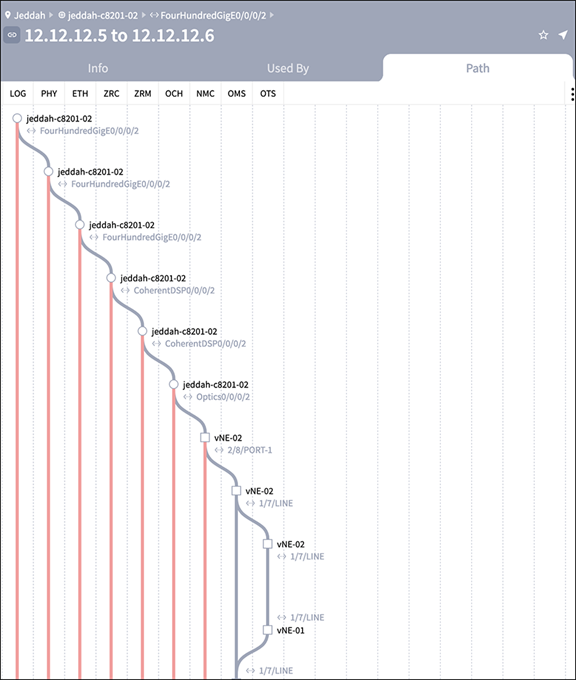

End-to-end circuit assurance from router to the optical OLS

2. Simplified, accelerated network service design and provisioning

Network service design and provisioning processes are commonly fragmented into parallel tasks owned by separate teams in different IP and optical organizations. The PoC tests demonstrated the Routed Optical Networking reference architecture simplified service design and provisioning tasks by eliminating unnecessary hardware. The automation layer enabled complete end-to-end visibility of the new network service paths. Endto-end provisioning becomes a single task with a single pane of glass. Such a unified view allows one team to effectively complete design, provisioning, and troubleshooting tasks without service layer fragmentation. Specific benefits include:

● Reduced provisioning and validation errors via simplified circuit layout records.

● Reduced service layer–based timeline fragmentation.

The proof of concept also demonstrated how stc personnel can add and remove capacity using a single User Interface (UI), which provides greater operational simplicity. Bundled interfaces were also tested, where two different OpenZR+ 400G links were transmitted via different OLS. These two links created a single 800-Gbps total capacity between Jeddah and Riyadh, as shown in Figure 11.

Multilayer service provisioning and rollback for Routed Optical Networking

3. Improved reliability, network troubleshooting resolution, and repair (service assurance)

Network troubleshooting and repair organizational models and systems are highly varied between carriers. As such, even minor changes to procedures, responsibilities, or handoffs can create unintended negative consequences.

Network repair teams should expect considerable improvements in many areas. Examples include:

● Increased reliability: Fewer points of failure in optics, transponders, OTN modules, etc.

● Network monitoring with fewer alarms: Reducing correlation complexity and increasing failure diagnosis speed/accuracy.

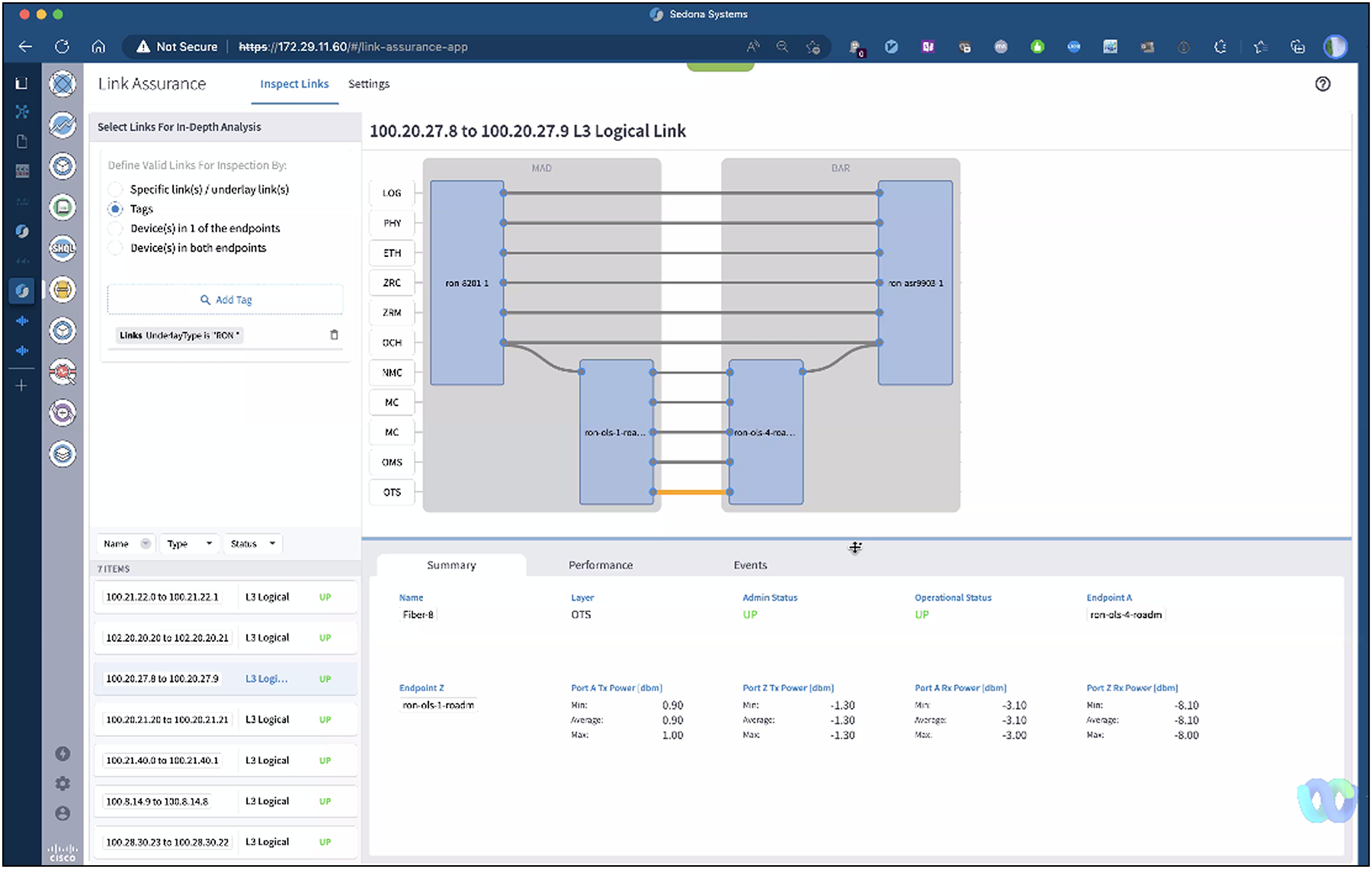

● Network repair: Crosswork HCO provides multilayer visibility. NOC teams can identify an underlying fault and quickly correlate alarms and tickets across multiple network layers. ZR/ZR+ optics are significantly less challenging and less expensive to identify faults accurately and replace.

● Link Assurance: The Link Assurance application allows you to visualize any IP or Ethernet links across ZR and OLS with performance in all layers—that is, Routed Optical Networking links. This all-in-one app is used for analysis of router-to-router or OT-to-OT link across ZR/+ pluggables and optical line systems and enables you to view aggregated link status as propagated from all layers, and drill down to performance and events history per link.

Link Assurance

While Routed Optical Networking architecture potentially brings widespread benefits to network repair teams, it also introduces process disruption that requires addressing. Notable examples include:

● Network monitoring: As mentioned earlier, large and complex organizational structures rely on strict scope boundaries to minimize inter-NOC interference. Moving the transponder functionality to the router in the Routed Optical Network service path will require changes in alarm reporting and labeling (through the IP SDN controller) to trigger the ticketing systems.

● Network repair: Legacy transponders often serve as a convenient demarcation point for isolating sections and applying loopbacks. Without this demarcation, NOC scope, visibility, or process changes must be modified to enable efficient repair. Fortunately, a well-designed automation layer helps mitigate these issues.

One of the most complex problems in multilayer operations is troubleshooting bundled interfaces. In the PoC, we analyzed the situation where errors were observed in one or all the members of an Ethernet bundle. Using the Crosswork Hierarchical Controller, the exact cause of the failure could be identified even if the IP connectivity was still active.

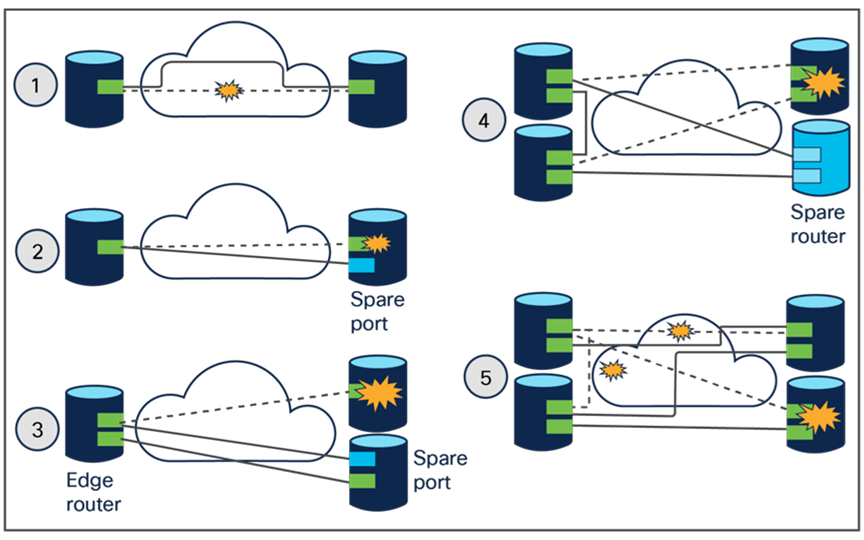

4. Rationalized infrastructure through multilayer restoration and network planning

Routed Optical Networking in conjunction with Hierarchical Control and combined visibility across IP and optical planes enables new approaches to network multilayer restoration:

1. The router can restore service arising from failures in the optical domain by leveraging the same router interfaces at both ends.

2. The router can restore service from node port failures or the link between the router and the OLS.

3. The router can restore edge element capacity from a failure of an aggregation element.

4. The router of core network topology can restore service from a failure of a core element.

5. The router can recover from a large-scale disaster involving an entire PoP, multiple fiber links, or multiple elements.

Multi layer restoration mechanisms

When full multilayer restoration mechanisms are deployed, a single spare interface is needed at each router with a transponder attached to it. Upon failure of a port, the extra port takes on the personality of the failed port, and the link is re-established. There is no need for IP layer protection (capacity) since both optical and port failures are dealt with using Routed Optical Networking restoration mechanisms as shown in Figure 14. These restoration scenarios are potential options that need to be further explored.

stc, in collaboration with Cisco, has conducted a proof-of-concept lab trial and TCO analysis of the Routed Optical Networking based IP/optical convergence architecture.

The key findings are summarized as follows:

● From the TCO analysis, there is a large potential for stc to achieve significant OpEx and CapEx reductions with the Routed Optical Networking approach as convergence of the IP and optical layers reduces the number of devices, positively impacting power consumption and footprint requirements. Network modeling shows benefits of up to 45% power reduction, 70% real estate savings, and 55% CapEx savings.

● Using network automation tools improves the utilization, resiliency, and flexibility of the network while helping to control costs.

● The Converged SDN Transport architecture combined with Crosswork automation changes complex multilayer and multivendor infrastructure into a unified, easily controlled network. stc will benefit from a network automation platform that accelerates network planning and designs, simplifies implementation, and proactively operates and optimizes the network.

● A well-prepared and carefully executed transition plan will be needed to redesign processes and address potential points of friction arising from the existing organizational structures. In particular, stc’s engineering and operational teams will need to embrace and execute these changes.

As mentioned previously, the ultimate target of the collaboration between stc and Cisco is to define a feasible multivendor and multilayer IP/optical converged metro architecture. Therefore phase 2 of the PoC will introduce third-party IP routing platforms and ROADM-based OLSs from other stc incumbent transport vendors and their respective domain controllers. The findings of this phase will be the subject of a separate white paper.

1. Cisco Routed Optical Network: Pioneering the IP and Optical Transformation: www.cisco.com/c/en/us/products/optical-networking/white-paper-sp-ip-optimized-opticaltransport.html.

2. TIP OOPT MANTRA White Paper: “IPoWDM convergent SDN architecture - Motivation, technical definition and challenges”, v1.0, 31 August 2022 https://telecominfraproject.com/wpcontent/uploads/TIP_OOPT_MANTRA_IP_over_DWDM_Whitepaper-Final-Version3.pdf.

3. TIP_OpenTransportArchitecture-Whitepaper_TIP_Final.

stc contributing authors: Ashraf Sattar, Infrastructure Architecture Professional and Abdullah Albargan, Transport and Fixed Access Architecture Section Manager.

Cisco Systems contributing authors: Valerio Viscardi, Principle Architect and Roque Gagliano, Technical Solutions Architect and Riad Kyriakos, Technical Solutions Architect.

Feedback

Feedback