Do Not Let E-Communication Compliance Be a Tragedy White Paper

Available Languages

Bias-Free Language

The documentation set for this product strives to use bias-free language. For the purposes of this documentation set, bias-free is defined as language that does not imply discrimination based on age, disability, gender, racial identity, ethnic identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and intersectionality. Exceptions may be present in the documentation due to language that is hardcoded in the user interfaces of the product software, language used based on RFP documentation, or language that is used by a referenced third-party product. Learn more about how Cisco is using Inclusive Language.

To B or not to B, that is the question: Whether ’tis nobler to have BYOD or corporate-owned mobile devices.

That is not quite how Shakespeare said it in Hamlet, but it is how he might have said it if he was a financial services compliance officer nowadays.

Today, compliance officers and chief risk officers, along with lots of other stakeholders, have to contend with the alphabet jargon of communication device strategies, from “bring your own device” (BYOD) and “choose your own device” (CYOD) to “company-owned/personally enabled” (COPE) and “company-owned/business only” (COBO). All strategies come with the goal of helping the company comply with strict financial services rules and regulations on communication. But when it comes to devices in the workplace, companies are finding it hard to strike a balance between “productivity” and “compliance.”

| BYOD |

Bring your own device |

| CYOD |

Choose your own device |

| COPE |

Company owned/personally enabled |

| COBO |

Company owned/business only |

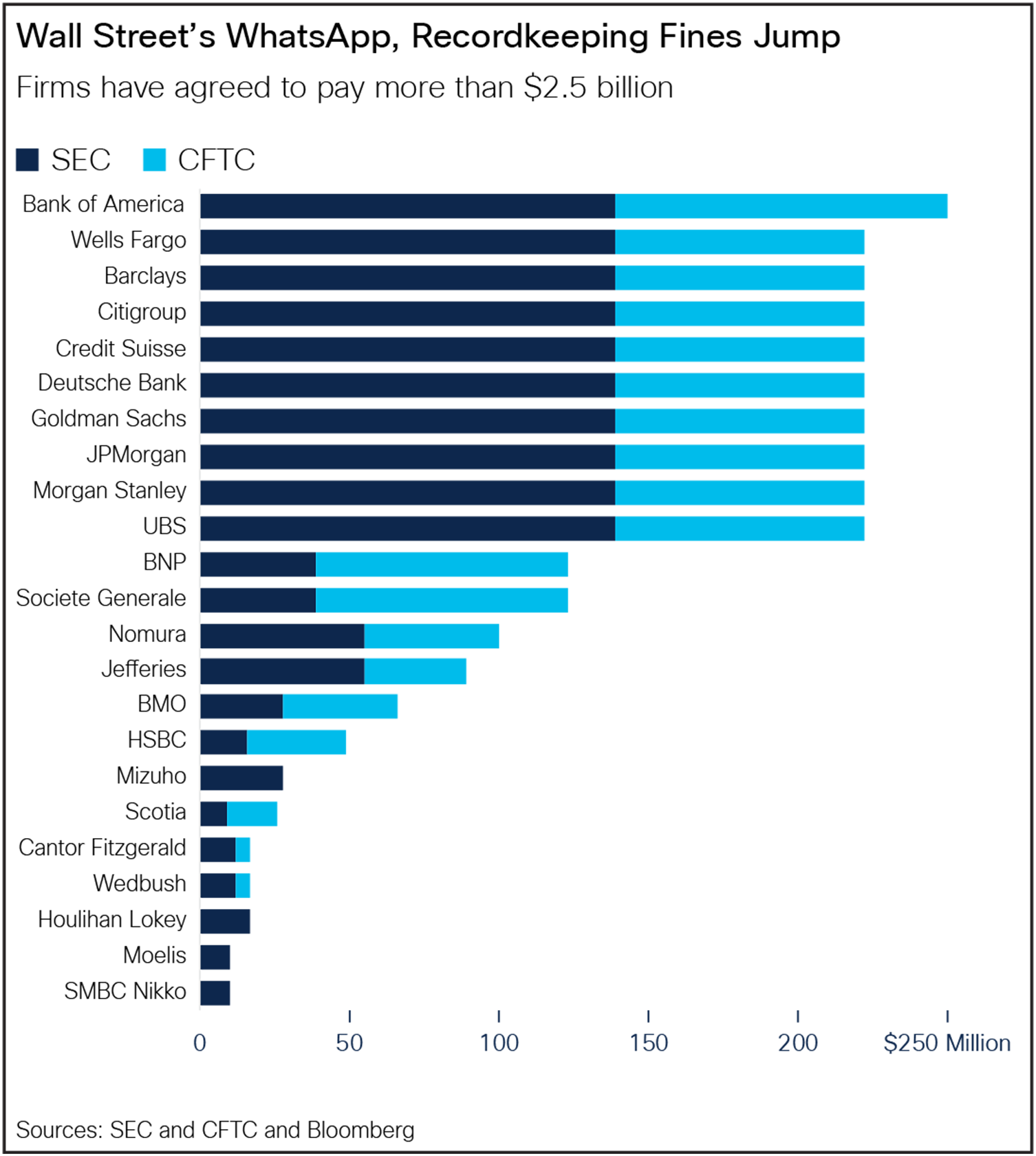

The need for this balance has taken on the utmost importance since the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) began fining financial institutions for using unauthorized communications channels and not recording those communications. The punitive financial damages so far are more than $2.5 billion (see figure 1) over the last three years, more or less since Covid upended workplace dynamics. The large punitive fines, which were almost unheard of before 2020, are just getting started in this age of hybrid work and plethora of communication channels.

Wall Street’s WhatsApp, Recordkeeping Fines Jump

Communications compliance requirements in financial services have always been very strict and are even tougher for certain segments such as capital markets, trading, investing, and insurance. Fast forward to today, and the financial services sector faces more regulations than ever before. This is due not just to different regulatory bodies but also to district, state, national, zonal, and even industry agencies. With the vast array of digital communication channels—mobile phones, text and chat, video, social media—compliance can be overwhelming.

Communications compliance regulations

The most common financial services compliance laws fall into two camps:

● Surveillance and supervision: These laws govern internal policies, review, audit trail, retention, and internal monitoring.

● Digital communications: These deal with content, audiences, and communication channels.

The main U.S. laws that impact financial services are from the SEC and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA).

● Securities and Exchange Act, Rule 17a-4(b)(4). This law requires broker-dealers to keep the originals of all the communications they receive. They must also keep copies of all communications they send that are related to “business as such” for at least three years. For the first two years, these records must be kept easily accessible. Updated Rule 17a-4 requires firms to retain and preserve all transactions and official business records, which includes all communications. These electronic records must be stored in a secure, non-erasable place.

● Commodities Future Trading Commission, CFTC SEA 15 F (g) (1). For the trading of commodity futures, broker-dealers must keep all daily trading communications related to security-based swaps, including email, instant messages, phone calls, and social media. All regulated records must be kept for the period required by the commission.

● FINRA Notice 10-06. This law requires firms to adopt policies and procedures to ensure that people who communicate for business via social channels are properly supervised. Anyone communicating through these channels must also be provided with training. And they must not put investors at risk.

● FINRA Notice 07-59. Similar to 10-06, this notice provides additional guidance on reviewing and supervising electronic communications.

Companies are at fault and liable for the fines when the SEC or FINRA finds them in violation of these regulations. These violations are not always due to a lack of internal controls and company policies and trainings; sometimes they arise from unauthorized use by employees. The largest fine to date given to one firm has been Bank of America for a total of $225 million. Not all financial institutions are excusing employees violations in these situations; some are passing along penalties to those who did not uphold the policies they committed to.

Morgan Stanley, is one example has taken action against its own employees in the form of clawbacks. They held training sessions explaining when bankers should move communication from personal devices to company communication channels, and instituted a penalty system. Penalties are scored according to a points system that considers the number of messages sent, the banker’s seniority, and whether they received prior warnings. They are either clawing back funds from previous bonuses or deducting money from future pay—with penalites ranging from a few thousand dollars up to six figures.

In certain cases, compliance violations and putting your institution at risk can result in termination of employment. Goldman Sachs fired transaction banking. executives, including the head of a business unit, over compliance lapses. Correspondingly, they terminated several leaders from this unit who communicated on unauthorized channels and didn't comply with an internal review. Credit Suisse, HSBC, and Morgan Stanley have all let some of their top commodities traders go over their use of personal apps.

It was once thought that fines would be limited only to financial regulators or to the United States, but that has not proven to be the case. Ofgem, the U.K.’s energy regulator, fined Morgan Stanley £5.4M ($6.9M) due to communications on energy market transactions made by wholesale traders on privately owned phones in a breach of rules designed to protect consumers, ensure market transparency, and prevent insider trading.

This fine and the source of the penalty may send “shock waves” through the banking industry, Rob Mason, the director of regulatory intelligence at Global Relay, told Bloomberg. “It puts firms on warning that it’s not just the financial regulators they need to be wary of,” said Mason. The Morgan Stanley energy traders discussed transactions over WhatsApp on privately owned phones between January 2018 and March 2020, and the bank failed to record and save those communications.

What really is the challenge is not the two types of communications that are regulated—calling and messaging—but the conduit: the mobile phone. Prior to the smartphone, few people considered using their personal mobile phones for business. The BlackBerry created a market for business-purpose devices. Although the BlackBerry is long gone, today, with the modern conveniences of Apple and Android smartphones, the alphabet soup of BYOD to COBO has gotten complicated.

From a business perspective things are changing too. Workforce dynamics are dictating a shift from on-premises calling to cloud calling, and this shift is revolutionizing the way businesses communicate. On-premises calling systems required substantial investments in hardware, maintenance, and skilled IT personnel. Cloud calling eliminates the need for physical infrastructure by using virtual servers and software hosted in the cloud. This transition offers numerous benefits, including scalability, cost-effectiveness, flexibility, and enhanced collaboration.

Cloud calling allows businesses to scale their communications systems effortlessly, adapting to changing needs and expanding their operations. It also reduces upfront costs, as businesses no longer need to purchase expensive hardware. The seamless integration of voice, video, and messaging features enhances collaboration and productivity, but it can come at a cost for communications compliance monitoring.

In addition to the mobile phone, the other culprit in violations of communications laws is off-channel messaging. This refers to communication channels that are not the primary platform or medium for customer interactions. It includes channels such as email, SMS, social media, and messaging apps. Off-channel messaging allows businesses to engage with customers on their preferred platforms and provide personalized, timely responses.

By leveraging off-channel messaging, most likely with BYOD phones, businesses can enhance customer satisfaction, improve response times, and create a seamless and convenient customer experience across multiple channels. It offers flexibility and convenience for both businesses and customers, leading to better communication and stronger customer relationships. At issue, though, is that these are unrecorded channels, so even though a customer may prefer these channels, they can cost a company.

Regulatory agencies don’t differentiate between business-related text messages that happen over BYOD phones and those sent over company-issued devices. Regulators mandate that communications using channels such as WhatsApp and Signal are recorded. However, the privacy of both the employee and the client will end up as a casualty if the company doesn’t work to steer clear of personal information.

Best practices for financial institutions

Compliance laws for communications are complex and constantly changing. To stay compliant, a company should consider adopting these best practices:

● Determine which laws are relevant to your institution.

● Have a clear understanding of how those laws are evolving.

● Hire compliance officers or consultants to help you understand how those laws impact your management of digital communications.

● Evaluate your enterprise compliance solution with all stakeholders to see if it meets compliance requirements for all your communications channels.

● Review corporate policies and procedures for the use of communications devices and platforms, including BYOD.

● Implement and review employee compliance training programs.

In reality, one of the most effective ways financial institutions can protect themselves is by training employees to never use their personal devices for business. It sounds simple in theory but is not easy to implement. Each device strategy (BYOD, CYOD, COPE, COBO) has its own pros and cons in terms of cost, convenience, security, and logistics. These make the decision-making process and how to protect a financial institution very challenging.

We’ll likely see more regulatory attention in this area in the United States and abroad focus on both global financial services and smaller institutions. Regulators will probably increase fines for repeat violators and cite more instances of “failure to supervise” as well.

So how do companies strike the right balance between securing communications and allowing convenience? Implementing some of the best practices mentioned above and finding a partner that can help you comply with laws related to recording and recordkeeping, no matter what mobile device communications strategy is deployed, is an important next step in the process. Taking these actions could prevent your digital communication plan from becoming another Shakespearean tragedy.